From war to warmth:

Refugee teens find a haven and hope at Global Village School

By Maureen Downey

Atlanta Journal Constitution, March 14, 2010

In her poem about Kakuma, a sprawling camp of 61,285 African refugees in northwestern Kenya, 15-year-old Amina Osman begins, “In Kakuma life is pain. I am five and life is pain.” She ends her poem on a far happier note, “I am 16, life is shining.” A Somalian refugee, Amina now attends the Global Village School, which opened in August to educate teen survivors of war. The refugee students rise early to take buses and trains to the downtown Decatur school; one girl begins her trek at 4 a.m. In many households, everyone rises early because the parents travel in van pools to chicken processing plants in Gainvesville.

“The girls coming here want to have an education,” says teacher Yang Li, one of the school’s two full-time teachers. Along with a part-time administrator, the teachers are the only paid staff at the school, which capitalizes on a daily stream of volunteers from the community and nearby colleges. The school grew out of a Saturday class started for the older siblings of pupils at the International Community School, a public charter school for refugee children that goes to 6th grade.

From an initial class of five teenage girls who had been child carpet workers in Afghanistan, the nonprofit Global Village School now teaches 30 students in an intense, extended five-day program girded by grants and donations. Many students attended school only sporadically while moving between countries and refugee camps. Their English is halting; their stories heartbreaking. Some have lost family to violence. Others have come here without their parents and yearn to see them again.

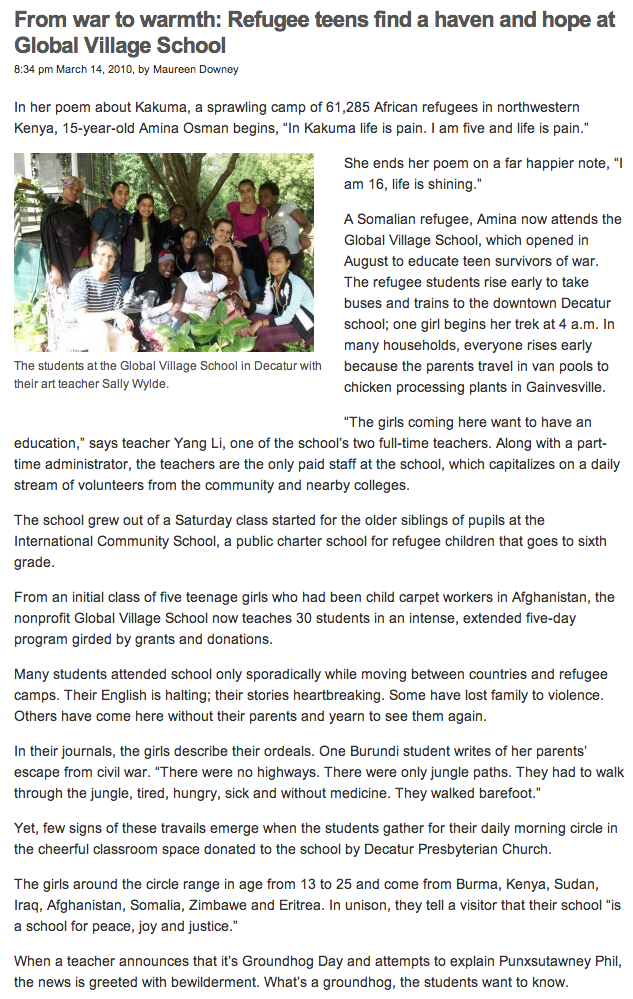

In their journals, the girls describe their ordeals. A Burundi student writes of her parents’ escape from civil war. “There were no highways. There were only jungle paths. They had to walk through the jungle, tired, hungry, sick and without medicine. They walked barefoot.” Yet, few signs of these travails emerge when the students gather for their daily morning circle in the cheerful classroom space donated to the school by Decatur Presbyterian Church. The girls around the circle range in age from 13 to 25 and come from Burma, Kenya, Sudan, Iraq, Afghanistan, Somalia, Zimbawe and Eritrea. In unison, they tell a visitor that their school “is a school for peace, joy and justice.”

When a teacher announces that it’s Groundhog Day and attempts to explain Punxsutawney Phil, the news is greeted with bewilderment. Their knowledge of American folklore and fauna is limited, but the students have other extraordinary aptitudes, including foreign language skills. Many speak three languages, a byproduct of the multiple refugee camps where they spent their childhoods.

They enroll at GVS to sharpen their English and math skills so they can move into a traditional public school or college. Several hope to attend Agnes Scott College down the street, where they walk every day to eat lunch in the dining hall. At a table in the dining hall over pizza and salads, five GVS students talk about their education. Two Afghan sisters in their 20s have no formal schooling, having fled with their families to India where they worked as seamstresses. They could not attend school because of the tuition costs, they explain.

But Zuhal Noori, 18, of Afghanistan and her sister Anousha, 13, attended school in Pakistan because their parents ran a school. “I like this school now,” says Zuhal. “The teachers are very kind to us. I want to learn English so I can go to college.” The students understand the imperative for English fluency as they see how it holds back their parents from finding jobs.

At monthly teas, the girls show off their work, musical talents and writings to invited guests. At the recent March tea, students stage an impromptu auction for their artwork to raise the last few hundred dollars for a field trip later this week to Washington. An opening bid of $10 for a colorful collage shoots to $125. While in the nation’s capital, the girls still have hopes of somehow meeting President Obama, who inspires them because of his own reliance on education to transform his life. At the tea, they read the letters they have sent to the president in the hopes of winning an audience. Reading from her letter, Zuhal says, “I learned from you how to make the impossible become the possible.”

![]()