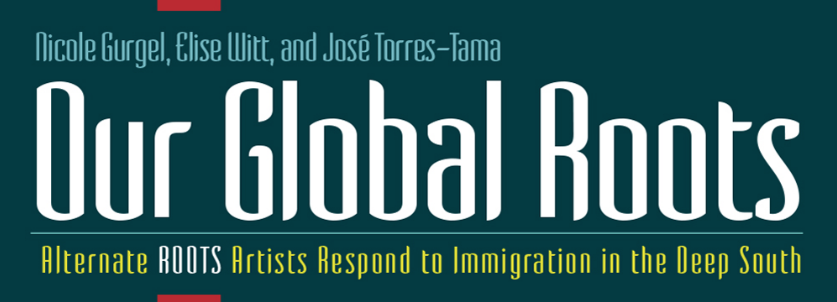

Read the article and whole interview online at Imagining America – http://public.imaginingamerica.org/blog/article/our-global-roots-alternate-roots-artists-respond-to-immigration-in-the-deep-south/

Elise and the Global Village Project, along with Ecuadoran/New Orleans performance artist José Torres-Tama,are featured in this article for Public a Journal of Imagining America, exploring higher education and public engagement.

For the past 40 years, Alternate ROOTS has been a champion of, and resource for, artists, cultural workers, and progressive movement building in the southern United States. Immigration to the South has increased dramatically since the early nineties and this boom continues through the present. According to the Migration Policy Institute, four of the five states with the largest percentage growth of immigrants between 2000 and 2012 were in the South (Zong and Batalova 2015). As a network of artists committed to creating work rooted in community, place, tradition, or spirit, it is vital that we are allied with the South’s immigrant communities and invested in globally engaged creative practice domestically.

This year, two of Alternate ROOTS Partners in Action projects shine a light on the experiences of immigrant communities in the Deep South. Both artists are themselves multilingual immigrants. Elise Witt, a Swiss-born daughter of Nazi Germany survivors, serves as the director of music programs at the Global Village Project in Decatur, GA. Drawing on her 40-plus-year career as a musician, Witt is working with a team of educators and artists to develop curriculum that empowers teenage female refugee students to navigate their new world with confidence and creativity. In New Orleans, Ecuadorian-born, New York/New Jersey-raised Torres-Tama employs the poetry, visual, and performance art practices he has honed over decades to ensure that the enormous contributions Latina/o immigrants made to post-Katrina reconstruction are not forgotten. Earlier this year, Nicole Gurgel, ROOTS’ content developer, spoke with these longtime members about their globally engaged creative practices.

By bearing witness to immigrant experiences in the South, Witt and Torres-Tama’s collective body of work resists and complicates the black/white polemic that has long defined both the region and the nation’s racial paradigm. Positioning their work within the context of European colonization, cross-Atlantic slave trade, and late-twentieth-century US imperialism, Witt and Torres-Tama reveal the ways in which global conflict and resistance to it has been, and continues to be, woven into the fabric of the South. As artists, their work not only illuminates these issues, but also underscores the power and value of engaging with them through the arts.

Music as Metaphor

A Global Perspective on Harmony

Nicole Gurgel:

I asked you to open this conversation by singing a song that resonates with the idea of globally engaged creative practice. Would you share one with us?

Elise Witt:

“English Is Weird” is a song that I wrote for my students at the Global Village Project (GVP). I wrote it to let my students know that my experience learning English parallels theirs, and that the reason they’re having a hard time learning English is that the language makes no sense—it is not logical! The song has four harmony parts. The first part is an exercise in articulation, “Lips, teeth, tip of the tongue, roof of the mouth, articulate.” The second part says, “My mouth feels funny when I speak English.” In the third part, we tell it like it is, “English is weird.” And the fourth part reflects my love of language as music, just the pure sounds: “I love to talk even when it doesn’t mean anything.” All four of these parts stack on top of each other in polyrhythmic harmony, a practice I find myself using a lot. After we’ve learned and enjoyed all these different parts, everyone comes together singing “listen, listen, listen” in four-part, interesting, not totally expected, harmony.

Nicole Gurgel:

Would you introduce GVP and talk about the vision you hold for the music program?

Elise Witt:

GVP is a special-purpose middle school for teenage refugee girls from Afghanistan, Burma, Congo, Liberia, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Iraq, Nepal, Somalia, Syria, and Central African Republic. It is truly the height of imperialistic irony when we welcome these refugees from precisely the countries where our global policies have led to war and chaos, creating millions of refugees. The students and their families live in the community of Clarkston, which has become the most diverse city in the entire United States. There are many challenges the families face upon arrival. But perhaps even more significant and overwhelming are the challenges they face once they have passed the six months of refugee aid, and are basically left on their own to support their families and pay back their passage. There are many agencies that have formed to help the refugees navigate systems like physical and mental health care, housing, transportation, and education. That is how the Global Village Project was born. GVP’s mission is “to develop a strong educational foundation for each student within a caring community using a strengths-based approach and intensive instruction in English language and literacy, academic subjects, and the arts.” So I’m using singing to teach English—and everything else! The school is in its sixth year, and I started teaching there halfway through their first year. Since then, I’ve been developing a music program that isn’t just a music program. It’s about creating an arts-integrated environment. It’s been a beautiful, amazing, interesting, and challenging journey for me, because I’m not formally trained as a music teacher, nor as an ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages) teacher. However, everything that I’ve done in my life up to this point has led me to this place. My training has been “in the field,” so it’s interesting to reflect on how I’m in the perfect place at the perfect time, both for myself in my development as an artist, and for the school in its development as an arts-integrated environment.

Nicole Gurgel:

In what ways does your long career as a globally engaged artist inform your work at GVP?

Elise Witt:

When I say I’ve been led to do this work, what I’ve come from is many years as a teaching artist for arts councils and community organizations around the country, bringing concerts, workshops, and residencies to K–12 schools, as well as colleges and universities. The dual focus has always been getting students excited about language and culture through singing and creating our own original songs.

Nicole Gurgel:

Would you share a story from this path?

Elise Witt:

In the early nineties I was invited to Dalton, Georgia, the “carpet capital of the world,” to spend a week doing concerts and workshops in each of the city’s elementary schools. What they failed to tell me before I arrived was that, over the preceding years, because of the carpet industry, the population had completely transformed. It was now somewhere between 60–80% Spanish-speaking immigrants, many of whom did not speak English. Luckily, Spanish is one of the languages I speak, and since my sponsors had not prepared me for this situation, I turned to the students for direction. Together we improvised a solution. We worked out a process of “changing channels”—switching back and forth between English and Spanish, translating back and forth. The thing that was interesting to me, and curious, was that the monolingual English speakers did not understand the concept of translation. They thought they were missing something every time we spoke in Spanish, whereas the Spanish speakers were used to this constant, everyday, all day long, translation process. Together, these students shifted that experience to create an understanding about language and translation between the bilingual and monolingual students. The solution that the students and I worked out is something I would like my work to be doing: to take English and Eurocentric culture out of the center, out of the central authority. My song “English Is Weird” seeks to do just that. It’s a way to clear the space, so that non-English speakers relate to the very real difficulty of learning this crazy weird English language, while English speakers can also appreciate the humor. It’s a good way to shift the center and open the circle.

Nicole Gurgel:

Harmony is so important to your work. Can you talk about how harmony relates to your globally engaged practice?

Elise Witt:

In some way, all my work is about harmony, musical and global—it’s such a great metaphor for what we’re trying to create in the world. I define harmony as two or more parts that come together and are “pleasing” to the ear. Pleasing is in quotes because harmony is both subjective and cultural. What is pleasing to one ear may be strange to another. There are so many different kinds of harmony in the world, from central African rain forest chants and Bulgarian women’s tight note clusters to Tuvan throat singing, Tibetan monks’ chants, and Southern gospel music. The opportunities for exploring harmony around the world are endless. In all my workshops and classes with young people and adults, we explore music by improvising and we learn songs without written music, using our ears and our bodies. It is amazing how much faster and deeper singers learn when they are not attached to paper. I always give students the opportunity to experience “polychotic listening,” listening to more than one thing at a time. When we have learned a piece that has multiple harmony parts, one group at a time goes inside the circle to just listen, without singing. With eyes closed they move their ears around to the different parts, the layers, and how they fit together. I like the image of harmony as a braid. We begin with individual hairs. Next, we divide the hairs into three separate strands. Finally, we weave the strands into a braid. At this point, we can see both the whole and its parts. Likewise, in creating musical harmony, first there is a big group made up of individual voices, each voice with its unique colors and tones. Next we divide the big group into smaller groups, each group seeking to sound like one voice, a perfect unison. In a formal or traditional choir, this would be equivalent to soprano, alto, tenor, and bass. Finally, we hear how those parts come together to create harmony, to create a song. And as singers, our ears can move back and forth from listening to our own individual part that we are singing, to hearing the whole, that is the song. Music is a beautiful metaphor for how we could live together, honoring our diversity while recognizing our common humanity. One plus one plus one equals one.

Nicole Gurgel:

You’ve mentioned that, as a teacher, you incorporate the T’ai Chi philosophy that “every teacher is a student and every student is a teacher.” At GVP you’re in a classroom with young women from around the world. Could you speak about what you’re learning from your students?

Elise Witt:

Being at GVP has been an interesting shift from my previous educational work. In some ways, I’m doing the same thing, but in a mirror version. Before, I was getting English speakers excited about opening to other sounds, other cultures, other music. Now I’m using music to help English language learners open to the sounds, culture, and music of the language of this new world they inhabit, and to learn how to navigate their new world through sound. How do they create a color palette of sounds to call upon as they’re learning this new language? And how do they want to sound? It’s about this idea that language is music and music is a language.

There are songs that we create, where we bring in words and phrases from every student’s culture. I’m working with a group of about 35 students, in which there are probably 80 languages; most of my students speak at least three if not four, five, or six languages. Being a language fanatic, my goal has always been to learn all the languages in the world. Well, at GVP I’m at least adding some phrases in Oromo, Karen, Arabic, Lingala, Kirundi—the list goes on!

We created a song at the beginning of the school year to get to know each other. It’s a song of welcome. It was originally inspired by an artist friend of mine, Masanko Banda, who is from Malawi. He told me, “In Malawi, when we greet each other, we say ‘I see you with my eyes, I see you with my heart.'” I started thinking about that, and created a little chant using that phrase. On top of that I layered a harmony using the word “welcome.” Then students taught us how to say “welcome” in their cultures. And we started layering the words polyrhythmically together to create a vocal collage. This version uses Arabic, Swahili, Hindi, Oromo (from Ethiopia), Kirundi (from Burundi), Pashto (from Afghanistan), and Karen, Karenni, and Chin (from Burma). I love how all of these rhythms can fit together and become that braid of harmony, where we’re singing in different languages—they all interweave, and welcome us in. One plus one plus one equals one!

Bearing Witness to Latina/o Immigrants and the Post-Katrina Rebirth

Verde Extra Alien Green. Poem and performance by José Torres-Tama.

Click to open pdf of poem.

Your personal history is a global one. How has this informed your work as an artist?

Having been born in Ecuador, South America, and come of age in the United States of North America, I consider myself a bilingual native of the Hemispheric Americas. While I am a naturalized US citizen, I often feel like a man without a country, especially since the heightened persecution of Arab Americans, Muslims, and Latina/o immigrants in this post-9/11 landscape where the foreign born is cast as the alien other and dehumanized.

If we dare to be honest, the first true “illegal aliens” in the Americas were the European colonizers. This beacon of democracy, the United States of Amnesia, was founded on the near genocide of native people, the enslavement of Africans to build empire, and the appropriation of the northern territories of Mexico, from Texas to California, in order to manifest imperial destiny. This is not myth. This is the historical legacy kept in the shadows, but it haunts the nation. Thus, it has a tough time living up to its mythic propaganda as capital of the free world because this troubling history affects the racial divides today.

The country embraces forgetting and urges its people to forget, as well.

I prefer to remember, because knowing the past allows me to better negotiate my future. I dare to carry my immigrant status like a badge of honor, and my mother was brave enough to make the leap from Guayaquil to New York City with her only child, a suitcase full of hope, and barely a few words in English with which to negotiate our passage. Upon arrival into the United States through Miami, I was immediately designated as a Permanent Resident Alien and we were given our green cards to go with the “alien” motif.

Thus, the Latina/o immigrant experience, the underbelly of the American Dream mythology, and immigrants’ rights drive the thematic thrust of my work. Post-Hurricane Katrina, I have been on a creative crusade to make sure that Latinas/os and the immigrant workers, who have been a big part of our reconstruction, are acknowledged in the post-storm narratives.

Can you talk about the work you have been doing in New Orleans to ensure that this happens?

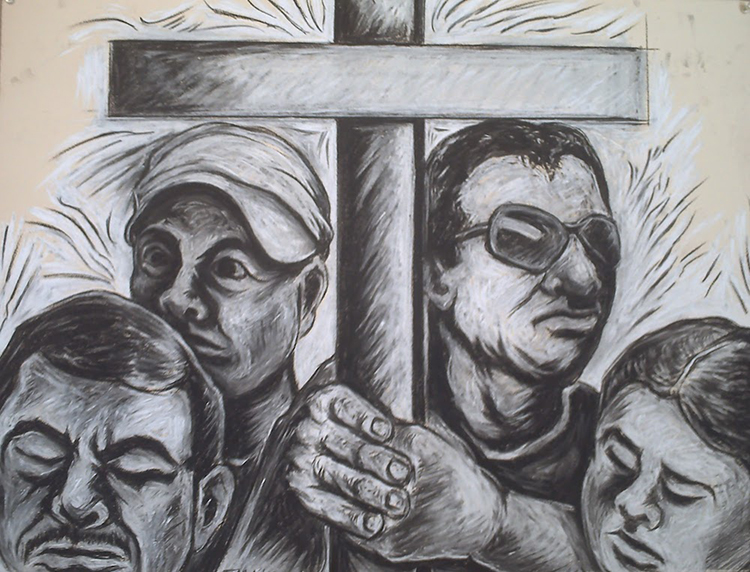

In the weeks, months, and years after Katrina, Latina/o immigrant laborers resurrected the city when it was in critical condition, on its deathbed. They cleaned out hotels, saved them from condemnation, and helped to reignite the engines of the tourist industry. They pulled out cadavers and cleaned the human waste from both the Morial Convention Center and the Superdome. Immigrants have been invaluable to our rebirth, but they suffer in the shadows. For many, it’s a science-fiction reality, and Latina/o immigrant workers here have become a ubiquitous labor force rendered invisible and suffering myriad human rights violations in the shadows. This is not unlike the millions of immigrant laborers across the country who pick the fruits and vegetables we all consume, bus the tables at restaurants, clean the corporate buildings in the late of night, and pick up the garbage in the early dawn—an army of laborers in the crevices, keeping the mega-matrix running. The “illegal aliens” label thrust upon undocumented people has dehumanized them for a system that readily exploits their labor.

In late October 2005, I met a young Puerto Rican man who told me he had worked for a contractor who promised to pay him and the other 300 men $3,600 for three weeks work. On the day before the big payday, the New Orleans Police Department raided their encampment—a gutted-out abandoned factory where they slept on cots. Acting like Immigration Agents on a raid, the police ran the workers away. This young man was the only one with citizenship papers, and when he confronted the contractor for his rightful pay, he was told that if he wanted his money he would have to go to Birmingham. He had no English to protest this violation and was left homeless. When I met him, he was with an even younger Mexican boy, maybe 17 years old, who was also a victim of this wage heist. Multiply $3,600 times 300 men, and you have more than a million in unpaid wages. This is one wage theft episode of hundreds taking place in New Orleans since Hurricane Katrina.

If we ever have the courage to investigate these violations, the post-Katrina era for Latina/o immigrant laborers will mark one of the most significant periods of labor abuse in this country’s history. In the summer of 2009, the Southern Poverty Law Center announced that 80% of the post-Katrina immigrant laborers of New Orleans were victims of wage theft. That is an atrocious number, but not surprising for a city that was once a major slave port when cotton was king.

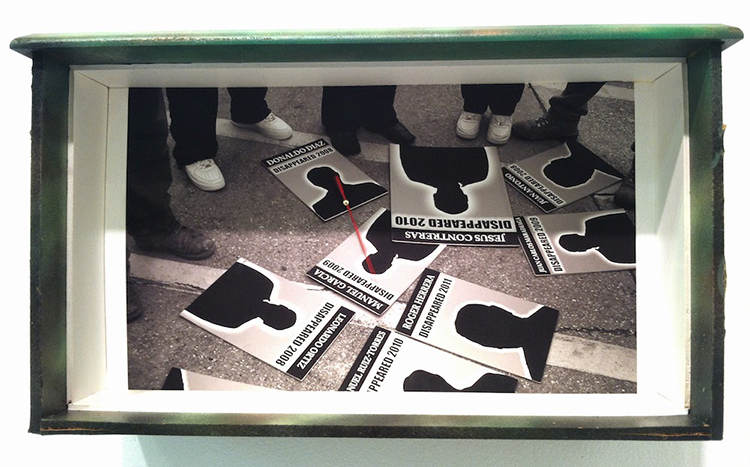

The group that has been doing incredible work to bring this message forward is the Congress of Day Laborers/El Congreso de Jornaleros, and they are actually immigrant reconstruction workers themselves. They have become protagonists and activists in their own fight for human rights because of the oppression they’ve experienced in the form of wage theft, police brutality, and deportations.

At a Congress of Day Laborers’ protest for International Workers’ Day on May 1, 2012, the wife of a day laborer gave emotional testimony that her husband suffered a Rodney King-style beating by Jefferson Parish policemen that February. After a week of searching, she finally located him in critical condition at a local hospital. Her husband was in a coma for two months from the beating, and his cranium had to be held together by multiple rods. Because of their undocumented status, they were afraid to report it. This fear and silence is common for immigrants who fear the authorities as much as they fear criminals who target them because they often carry cash on their persons from construction jobs.

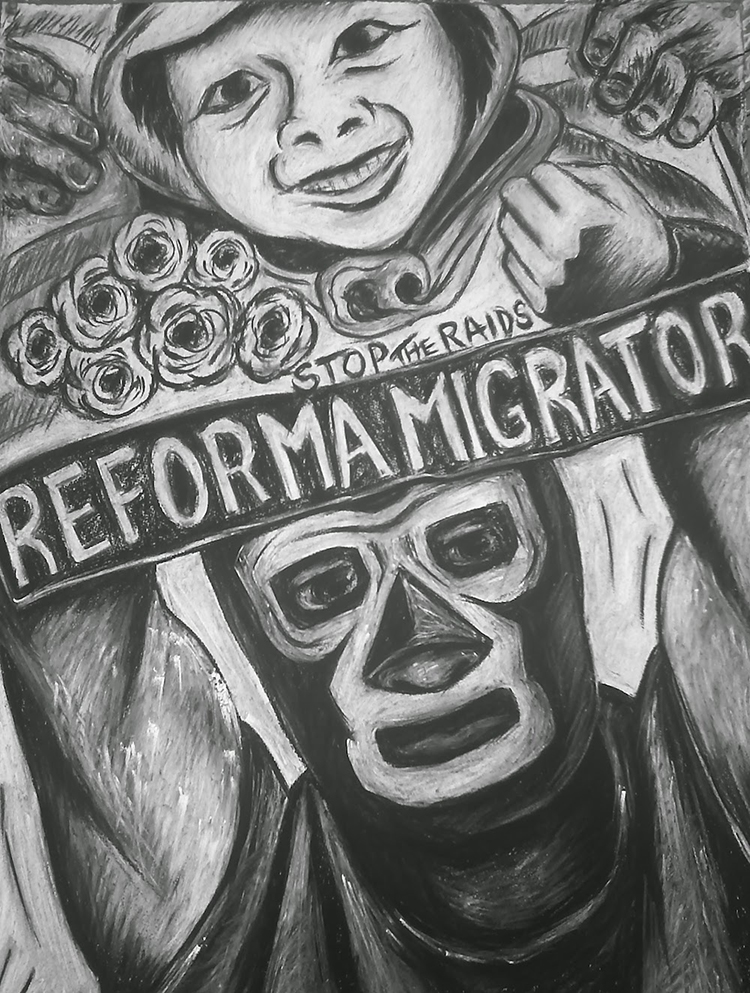

I have been fortunate enough to bear witness to this contemporary civil rights movement, photographing and filming protests since 2010. My performance piece, ALIENS, IMMIGRANTS & OTHER EVILDOERS (2010), is informed by stories of immigrant laborers. With the blessing of the Congress of Day Laborers, I developed a series of drawings and photographic assemblages calledSomos Humanos/We Are Human (2013) that chronicles this movement of immigrant workers fighting for their human rights.

I think the best any artist can do is to bear witness. In the Latin American tradition, the artist has a social responsibility to document and articulate the people’s struggle—la lucha de la gente. My art is driven by social justice concerns, and I hope that my creative work can serve to expose these difficult truths as we approach the tenth anniversary of the storm.

Do I remember correctly that your Partners in Action Project involves a taco truck?

Yes, it’s called the ALIENS Taco Truck Theater Project. Post-Katrina, food trucks became ubiquitous in New Orleans. Some came in from Houston and most were initially established here to feed the laborers. And I just thought: the food truck would be a great way to mobilize this work and create un Teatro Sin Fronteras, a mobile theater without borders, bringing Tacos y Actos to immigrant audiences. The taco truck’s motto is, “No Guacamole for Immigrant Haters!” It’s about creating an outdoor dinner theater for immigrant communities outside the Eurocentric theater paradigm, creating a cultural platform to explore the challenges immigrant communities face, and inspiring immigrants to take the mobile stage and perform their personal stories—becoming protagonists in their cause and breaking the silence.

It’s very much inspired by El Teatro Campesino, the theatrical arm of Cesar Chavez’s United Farm Workers’ Movement, and their tent shows on flatbed trucks in the sixties and seventies. Luis Valdez, El Teatro Campesino’s legendary founder, and his troupe went out in the fields and performed for immigrant farm workers, and made the plight of farm workers public with truck performances in front of California union halls. Valdez was actually inspired by Federico Garcia Lorca. Lorca felt that theater was being taken hostage by the bourgeois, and would take his troupe on trucks and perform for gypsy workers in the olive groves in Granada. Basically, it’s a means to get the work to the people and into the barrios, and to create work about the heroic nature of immigrants who have been continuously diminished and dehumanized.

As a longtime ROOTS member, how does your work add to or challenge what it means to be an artist-activist in the South?

I first came to ROOTS in 2000, when Alice Lovelace, then Executive Director, asked me to attend the annual meeting. I was deeply grateful to Alice because she reached out to broaden the race conversation and to include artists from the growing Latina/o population in the Deep South.

We need to engage in a paradigm shift and include a larger population of color that is affected by the lingering legacy of systemic and institutionalized racist practices in the South. The current social justice struggle in the South is more than just a black and white struggle. Latina/o immigrants are being targeted with the same racist vitriol that was once exclusively directed at African Americans. Racism has diversified and other people of color experience the lingering legacy of institutionalized white supremacy that still haunts our black brothers and sisters in the Deep South.

In 2011, Georgia—where Alternate ROOTS is based—passed one of the most draconian anti-immigrant laws in the country. Modeled after Arizona’s SB1070, the Georgia law and Alabama’s anti-immigrant bill that followed were set up to attack the immigrant community. All Latinas/os became suspects—whether you were with or without papers. If you were a brown Mestizo Latina/o or “Latina/o-looking,” the local police in both states could stop you and ask for papers. In Alabama, teachers were asked to become informants and alert officials if they believed their grammar school students were undocumented. South Carolina also joined this new Confederacy, and passed it’s own “Juan Crow Law” in 2011, in order to redirect a racist agenda towards Latina/o immigrants. Even more disturbing is that the language adopted is these new anti-immigrant laws resembles language in the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 and 1850 that imposed penalties on those who aided and transported runaway slaves. Substitute “illegal aliens” for “fugitive slaves” and you have a haunting legacy.

You’ve been a practicing artist since the eighties. What cultural and political shifts or non-shifts have you witnessed over the course of your career?

Much of my work is investigating the vestiges of colonization and its lingering shadows. Globally, the United States has positioned itself as the epitome of democratic nations, but it dares not look in the mirror. In Latin America, throughout the twentieth century, the United States has propped up dictator after dictator to protect corporate interests: Pinochet in Chile, Somoza in Nicaragua, Trujillo in the Dominican Republic, to name a few. The United States imposed Milton Friedman’s unfettered capitalism as “free market democracy” on our working class people and campesinos, and while the Swiss gave him a Nobel Prize, he gave Chile’s Pinochet capitalist brutality to supposedly eradicate communism. Naomi Klein calls it the “shock doctrine” in her New York Times best-selling tome (2007), and journalist Juan Gonzalez calls it the “harvest of empire” in his book (2000). The fallout is that millions of people are forced to migrate because US policies ravage our lands in Latin America and create economic and war refugees.

If we have any conscience at all, we need to ask ourselves, “What price are other people paying for the freedoms we enjoy as part of the empire?”

I’m a big believer in public activism and taking to the streets to collectively call out these injustices. It’s 2015, and having a multiracial president has not stopped the brutality against black and brown men. In fact, the biggest fallout towards people of color post-Obama was actually the brutalization of black men and immigrants across the country. And while Mr. Obama has decided to take executive action on Immigration Reform, this has not come from finally making good on his initial ’08 campaign promise, but because of relentless public demonstrations of millions of Latinas/os across the country. Young Dreamers and hundreds of undocumented people went on hunger strikes in front of the White House. Some chained themselves to its iron gates, shaming Obama’s administration and it’s brutal deportation apparatus. He’s deported more than two million immigrants—more than any other president before him. It’s a tragic metafiction reality that the multiracial son of an African immigrant ascends to the presidency and becomes the “Deporter-in-Chief.”

As an artist who’s socially engaged, I’m stunned by the dichotomies that persist in the so-called land of the free. And what we saw at the end of the year was the importance of taking it to the streets and challenging regressive beliefs. We have to question how far we have come when we still have to make a case that Black Lives Matter and that No Human Being Is Illegal!

We are all the people, and we are in desperate need of a major paradigm shift.

Conclusion

These creative, community-based projects emphasize the necessity of a global paradigm when developing publicly engaged art or scholarship with US communities. Globalized US communities are not a new demographic reality, but a continuation of this nation’s immigrant history and reflective of its global violences: colonization, slavery, and imperialism. Torres-Tama’s work documenting Latina/o immigrants’ civil rights battles in New Orleans underscores the ways in which the struggle of new peoples of color in this region mirrors older struggles. Wage theft and police brutality of immigrants, whose legal recourse is compromised by their citizenship status, is part of the legacy of state-sanctioned un(der)paid labor in the South. Witt’s work at the Global Village Project highlights the fact that the tens of thousands of refugees who have arrived in Decatur are from exactly those parts of the world where US policies have historically interfered, leading to war, chaos, and displacement. Both artists address the fact that institutional racism and anti-immigrant policies dehumanize entire groups of people whose labor is readily exploited by the same system that forces their migration and vilifies them upon arrival. Witt and Torres-Tama’s globally engaged practices speak to the necessity of evolving beyond the black/white racial paradigm so prevalent in the US imaginary, and examining the ways in which the old and continual struggle for civil rights in the South is reflected in the lives of these newly arrived Southerners.

As artists, Torres-Tama and Witt illuminate these truths aesthetically. Witt’s music and work at the Global Village Project reflects a complex, multiracial paradigm. Songs like the multilingual “I See You with My Heart” and the playfully critical “English Is Weird” create spaces of radical welcome. Through polyrhythm, what Witt calls “interesting, not totally expected harmonies,” and the belief that every voice has something to offer, her music affirms the possibility of multiple truths peacefully coexisting. Torres-Tama employs a vast repertoire of mediums—visual art, poetry, performance, and now a mobile Teatro Sin Fronteras—to bear witness to Latina/o immigrant experiences in the reconstruction of New Orleans. Locating these contemporary struggles within the long arch of US and Deep South history, he underscores the importance of holding the past and present together. In doing so, he echoes James Baldwin: “The great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us . . . history is literally present in all that we do” (1985).

Torres-Tama and Witt shed light on struggle, while illuminating a principle that Alternate ROOTS holds dear: as artists, the beauty we seek is bound up with justice. Last November, ROOTS Executive Director Carlton Turner published an essay on Americans for the Arts’ ARTSblog, whose title posed the question, “What Is Beauty Without Justice?” Acknowledging that aesthetics has a complex, hegemonic history, he describes ROOTS’s understanding of it as, “it’s not just where you end up, it’s also how you got there” (2014). This understanding of aesthetics—that process is as important as product and beauty devoid of justice is an empty prospect—is reflected in both Witt and Torres-Tama’s work. Torres-Tama’s Teatro Sin Fronteras almost literally reflects the idea of “it’s how you got there.” In meeting immigrant communities where they are, this mobile gallery and performance space emphasizes the power of art that is deeply embedded in and accessible to community. Witt “gets there” by building songs collectively, honoring every language and every person in the room. Through music and mobile teatro, these artists forge alliances with immigrant communities, create spaces of radical welcome, and bear witness to the beauty inherent in our struggle for justice.

Work Cited

Baldwin, James. 1985. The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, 1948–1985. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Gonzalez, Juan. 2000. Harvest of Empire: A History of Latinos in America. New York: Penguin.

Klein, Naomi. 2007. The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. New York: Picador.

Turner, Carlton. 2014. “What Is Beauty Without Justice?” ARTSblog. Americans for the Arts. November 19. Accessed February 1, 2015.

Zong, Jie, and Jeanne Batalova. 2015. “Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States,” Migration Information Source. Migration Policy Institute. February 26. Accessed February 26, 2015.